Sunday, December 3, 2006

Keep a good selection of earrings on hand to meet all your fashion needs

It’s amazing what a pair of earrings can do to your look! Earrings are the most important wardrobe accessory you can own. You’ll get great value from your earrings. Choose earrings that meet your life style, your personality, and your tastes. There is no point in buying a pair of trendy earrings that you’ll never wear because they don’t feel like "you".Earrings also make a great jewelry gift as

Friday, September 22, 2006

Silhouettes

“Shades are the truest representation that can be given of man” – Johann Lavater, 1804

“Shades are the truest representation that can be given of man” – Johann Lavater, 1804Shades, the old name given to silhouettes, became popular after about 1760 and were an outgrowth of the neoclassical revival. Silhouette artists were extremely influenced by both Johann Lavater and classical Greek art. Lavater, the father of the pseudo-science of physiognomy, believed that one’s internal qualities, emotions, intellect, capacity for achievement, and so forth, could be read from a profile of the face especially as a shade. Essentially physiognomy was the “science” of judging a book by its cover, but it was very popular with the producers and consumers of silhouettes. Ancient Greek black figure vases and red figure vases provided additional sources of inspiration and study for artists. For example, both Charles Rosenberg and Jacob Spornberg produced silhouettes in imitation of these silhouette-like vases. Silhouettes were produced on a variety of media including paper, plaster, and ivory.

Silhouette from Lavater’s treatise on physiognomy illustrating, “A man of business, with more than common abilities. Undoubtedly possessed of talents, punctual honesty, love of order, and deliberation. An acute inspector of men; a calm, dry, determined judge.”

Pair of unframed French mourning silhouettes, circa 1780, preumably representing a husband and wife. Both silhouettes are cut from black paper affixed to ivory and embellished with watercolor. Her silhouette bearing the inscription, "Il ne me reste que l'ombre," or "Only my shade remains," is surrounded by six tiny forget-me-nots.

John Miers (fl. 1760-1810) Silhouette of John Shore Lord Teigenmouth (1751-1834). He served as the Governor General of India from 1793-1797 and was made the First Baron Teigenmouth in the Irish Peerage in 1798. This Miers watercolor on plaster silhouette, c. 1800, is the earliest known portrait of John Shore. Price: $1400

Thomas R. Poole, wax medallion of Lord Teigenmouth, 1818, from the National Portrait Gallery.

George Richmond, watercolor of Lord Teigenmouth, 1832, from the National Portrait Gallery.

John Miers (fl. 1760-1810) Silhouette pair painted on ivory and signed "Miers" under the truncation. Price: $1800

John Miers (fl. 1760-1810) Silhouette painted on plaster and signed “Miers” under the truncation with braided hair surround and hairwork reverse. Unfortunately, cracked vertically. John Miers was the master of delineating the finely detailed diaphanous features of clothing.

J. H. Gillespie (fl. 1810-1838) Profile of English Lady c. 1815-20 bearing only the corner remnants of trade label #2. This profile is the type advertised as, "Likenesses, with the features neatly shaded on black grounds, in imitation of copper-plate busts, at 5s. each." He also offered bronzed silhouettes at 5s. and profiles "shaded in watercolor," that is full color profiles with his trademark blue brown crescent shading along the bottom edges of the miniature, for 7s. 6d. each. Gillespie advertised his work as "likenesses drawn in one minute" with the aid of "several mechanical and optical instruments" including a physiognograph, his version of the popular physiognotrace. Gillespie worked in America in the 1830s and at that time he charged 25 cents for silhouettes, 50 cents for the type of profile pictured below, $1 for bronzed silhouettes, and $2 for "features neatly painted in colors."

Silhouettes

“Shades are the truest representation that can be given of man” – Johann Lavater, 1804

“Shades are the truest representation that can be given of man” – Johann Lavater, 1804Shades, the old name given to silhouettes, became popular after about 1760 and were an outgrowth of the neoclassical revival. Silhouette artists were extremely influenced by both Johann Lavater and classical Greek art. Lavater, the father of the pseudo-science of physiognomy, believed that one’s internal qualities, emotions, intellect, capacity for achievement, and so forth, could be read from a profile of the face especially as a shade. Essentially physiognomy was the “science” of judging a book by its cover, but it was very popular with the producers and consumers of silhouettes. Ancient Greek black figure vases and red figure vases provided additional sources of inspiration and study for artists. For example, both Charles Rosenberg and Jacob Spornberg produced silhouettes in imitation of these silhouette-like vases. Silhouettes were produced on a variety of media including paper, plaster, and ivory.

Silhouette from Lavater’s treatise on physiognomy illustrating, “A man of business, with more than common abilities. Undoubtedly possessed of talents, punctual honesty, love of order, and deliberation. An acute inspector of men; a calm, dry, determined judge.”

Pair of unframed French mourning silhouettes, circa 1780, preumably representing a husband and wife. Both silhouettes are cut from black paper affixed to ivory and embellished with watercolor. Her silhouette bearing the inscription, "Il ne me reste que l'ombre," or "Only my shade remains," is surrounded by six tiny forget-me-nots.

John Miers (fl. 1760-1810) Silhouette of John Shore Lord Teigenmouth (1751-1834). He served as the Governor General of India from 1793-1797 and was made the First Baron Teigenmouth in the Irish Peerage in 1798. This Miers watercolor on plaster silhouette, c. 1800, is the earliest known portrait of John Shore. Price: $1400

Thomas R. Poole, wax medallion of Lord Teigenmouth, 1818, from the National Portrait Gallery.

George Richmond, watercolor of Lord Teigenmouth, 1832, from the National Portrait Gallery.

John Miers (fl. 1760-1810) Silhouette pair painted on ivory and signed "Miers" under the truncation. Price: $1800

John Miers (fl. 1760-1810) Silhouette painted on plaster and signed “Miers” under the truncation with braided hair surround and hairwork reverse. Unfortunately, cracked vertically. John Miers was the master of delineating the finely detailed diaphanous features of clothing.

J. H. Gillespie (fl. 1810-1838) Profile of English Lady c. 1815-20 bearing only the corner remnants of trade label #2. This profile is the type advertised as, "Likenesses, with the features neatly shaded on black grounds, in imitation of copper-plate busts, at 5s. each." He also offered bronzed silhouettes at 5s. and profiles "shaded in watercolor," that is full color profiles with his trademark blue brown crescent shading along the bottom edges of the miniature, for 7s. 6d. each. Gillespie advertised his work as "likenesses drawn in one minute" with the aid of "several mechanical and optical instruments" including a physiognograph, his version of the popular physiognotrace. Gillespie worked in America in the 1830s and at that time he charged 25 cents for silhouettes, 50 cents for the type of profile pictured below, $1 for bronzed silhouettes, and $2 for "features neatly painted in colors."

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

Tribe's tech plan a model program

Tribe's tech plan a model programMark ShafferThe Arizona RepublicSept. 19, 2006 12:00 AM TONALEA - While much of rural Arizona lags in an Internet void, the Navajo Nation is a leader among the nation's tribes in speedy connections.Renda Fowler, community services director for the remote Tonalea chapter east of Tuba City, says it never ceases to amaze her. As cattle graze outside her window and

Saturday, September 16, 2006

EPA whiffs power plant

EPA whiffs power plantProponents argue air is clean; opponents worry about mercurySunday, September 17th 2006By John R. Crane Journal Staff WriterSithe Global officials say the Desert Rock power plant would cap mercury output by at least 80 percent and would set a new standard for pollution controls for other energy facilities."The air, with or without Desert Rock, is getting signifi-cantly

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

New Miss Indian Nations crowned in Bismarck

New Miss Indian Nations crowned in BismarckThe fourteenth Miss Indian Nations is a descendant of Chief Standing Bear of the Ponca Tribe.Ponka-We Vickers, a member of the Ponca Nations of Kansas and the Tohono O'odham Nation, was selected from five nominees Saturday at the United Tribes International Powwow."I'm shocked that I was chosen," Vickers said after being crowned. "But I'm very humbled by

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

Billy earns the Miss Navajo Nation title

Billy earns the Miss Navajo Nation titleBy Natasha Kaye JohnsonDiné BureauJocelyn Billy of Chinle holds back tears of joy as she is crowned Miss Navajo Nation 2006-07 by Miss Navajo Nation 2005-06 Rachel James at the 60th Annual Navajo Nation Fair in Window Rock on Saturday night. Billy graduated from NAU and was crowned Miss Indian NAU while attending school thereWINDOW ROCK — Each year, one Din

Tax proposal would fund judicial, public safety facilities

Tax proposal would fund judicial, public safety facilitiesIncrease could generate $4M for Navajo NationBy Erny Zah The Daily Times FARMINGTON — A proposed 1 percent gross sales tax could add up to an estimated $4 million for Navajo Nation public safety and judicial facilities, according to the Navajo Tax Commission.Last week, the Navajo Tax Commission announced its support for proposed

Monday, September 11, 2006

Powwow will honor veterans

Powwow will honor veteransEvent to feature speech by Navajo code talkerSunday, September 10, 2006BY ELIOT BROWNOF THE JOURNAL STARedwards - An American Indian powwow honoring veterans will begin Friday, featuring a speech from a Navajo code talker who fought in World War II. The Gathering of Veterans Friendship Pow Wow, now in its third year, is hosted by the Seven Circles Heritage Center in

Thursday, September 7, 2006

Sepias and Allegorical Miniatures

Miniatures painted in sepia are another perplexing form of sentimental jewelry. There is a great deal of disagreement over what exactly a sepia is. I define sepias as miniatures painted in watercolor on ivory in either a shade of gray, brown, or black. The sepia paint may or may not be entirely derived from or include “dissolved” human hair, that is, hair that has been ground into a fine dust with mortar and pestle so as to be fit for a paint base. Like cameos, portraits of individual sitters or more frequently allegories may be painted in sepia. Because sepias depicting mourning allegories are by far the most common, it is generally assumed that all sepias were mourning jewelry. However, this is not the case. Sepias depicting shepherdesses, Greek gods, republican symbolism (personifications of liberty, liberty staff and cap, cornucopias, and other revolutionary insignia), domestic scenes, landscapes, friendship allegories, and risqué copies of French art are also common enough.

Miniatures painted in sepia are another perplexing form of sentimental jewelry. There is a great deal of disagreement over what exactly a sepia is. I define sepias as miniatures painted in watercolor on ivory in either a shade of gray, brown, or black. The sepia paint may or may not be entirely derived from or include “dissolved” human hair, that is, hair that has been ground into a fine dust with mortar and pestle so as to be fit for a paint base. Like cameos, portraits of individual sitters or more frequently allegories may be painted in sepia. Because sepias depicting mourning allegories are by far the most common, it is generally assumed that all sepias were mourning jewelry. However, this is not the case. Sepias depicting shepherdesses, Greek gods, republican symbolism (personifications of liberty, liberty staff and cap, cornucopias, and other revolutionary insignia), domestic scenes, landscapes, friendship allegories, and risqué copies of French art are also common enough. The Apotheosis of Daniel Legate, Jr.

Mourning sepia on ivory with mourner dressed in classical garb, a weeping willow, urn, chopped hair ground, and inscription on the plinth, “DANL. LEGATE JUN. OB: 10TH April 1791.” The cameo-like portrait medallions surrounding the memorial were a popular addition to cemetery monuments in the 1790s. The spirit of Daniel Legate reclines wrapped in clouds above the mourner and next to the inscription on the upper left edge, “WEEP NOT FOR ME.” The reverse composed of a hairwork ground covered with tiny gold stars. The hair of the deceased literally forms the heavenly ether, a symbolic union of body and spirit.

Mourning Sepia on ivory, circa 1780, with chopped hair, weeping willow, female mourner dressed in classical clothing, urn, and inscription on the plinth, "In Memory of a Beloved Father, JB.” The reverse is inscribed with the initials, “C.M.B.”

John Barry (fl. 1784-1827) Portrait sepia on ivory of father and daughter, c. 1785, with hairwork.

Charles Hayter (1761-1835) Maternal Allegory

I use the term "allegorical miniature" to denote full color miniatures that otherwise resemble sepias in their visual and thematic composition. This watercolor on ivory miniature, circa 1795, represents a mother with her son, dressed like Gainsborough's "Blue Boy," and daughter, dressed like Lawrence's "Pinky," resting on a bench in an Arcadian landscape.

Hayter served as Teacher of Perspective to Princess Charlotte. The above miniature displays Hayter's short, compact, oblique brush strokes, blue shading to the recesses of the face especially the corners of the eyes, and the blue, green, yellow color scheme borrowed from “Newton’s rainbow” and intended to resonate with “the cold part of the iris” (Hayter 1815). The Maternal Allegory likewise illustrates several of Hayter’s (1815) fourteen enumerated rules to be observed in shading:

Rule 1

The greatest distance in an open scene, with a clear sky, will always be the palest…

3 The nearest objects, or those in the foreground of an open scene, will have the darkest shades…

5 To adapt the picture to the power and properties of the eye, you must, on all occasions, lay as tender, gradual, and imperceptible a shade as possible, at each corner of a square or oblong drawing, blending it sweetly off towards the point of sight, so as to give the surface a concave apperance. The same should be done towards the margin of a circular drawing; always securing this natural concave effect.

6 Always begin with pale tint of the sky and distant masses of shade; and as you approach the foreground, increase the depth of the tint, observing to be light enough at first.

7 When you require additional strength of shade, do not take a darker tint for that purpose, but repeat the use of the original tint; strengthening the shades of all the degrees of distance with its own tint, or the object will press too forward.

Sepias and Allegorical Miniatures

Miniatures painted in sepia are another perplexing form of sentimental jewelry. There is a great deal of disagreement over what exactly a sepia is. I define sepias as miniatures painted in watercolor on ivory in either a shade of gray, brown, or black. The sepia paint may or may not be entirely derived from or include “dissolved” human hair, that is, hair that has been ground into a fine dust with mortar and pestle so as to be fit for a paint base. Like cameos, portraits of individual sitters or more frequently allegories may be painted in sepia. Because sepias depicting mourning allegories are by far the most common, it is generally assumed that all sepias were mourning jewelry. However, this is not the case. Sepias depicting shepherdesses, Greek gods, republican symbolism (personifications of liberty, liberty staff and cap, cornucopias, and other revolutionary insignia), domestic scenes, landscapes, friendship allegories, and risqué copies of French art are also common enough.

Miniatures painted in sepia are another perplexing form of sentimental jewelry. There is a great deal of disagreement over what exactly a sepia is. I define sepias as miniatures painted in watercolor on ivory in either a shade of gray, brown, or black. The sepia paint may or may not be entirely derived from or include “dissolved” human hair, that is, hair that has been ground into a fine dust with mortar and pestle so as to be fit for a paint base. Like cameos, portraits of individual sitters or more frequently allegories may be painted in sepia. Because sepias depicting mourning allegories are by far the most common, it is generally assumed that all sepias were mourning jewelry. However, this is not the case. Sepias depicting shepherdesses, Greek gods, republican symbolism (personifications of liberty, liberty staff and cap, cornucopias, and other revolutionary insignia), domestic scenes, landscapes, friendship allegories, and risqué copies of French art are also common enough. The Apotheosis of Daniel Legate, Jr.

Mourning sepia on ivory with mourner dressed in classical garb, a weeping willow, urn, chopped hair ground, and inscription on the plinth, “DANL. LEGATE JUN. OB: 10TH April 1791.” The cameo-like portrait medallions surrounding the memorial were a popular addition to cemetery monuments in the 1790s. The spirit of Daniel Legate reclines wrapped in clouds above the mourner and next to the inscription on the upper left edge, “WEEP NOT FOR ME.” The reverse composed of a hairwork ground covered with tiny gold stars. The hair of the deceased literally forms the heavenly ether, a symbolic union of body and spirit.

Mourning Sepia on ivory, circa 1780, with chopped hair, weeping willow, female mourner dressed in classical clothing, urn, and inscription on the plinth, "In Memory of a Beloved Father, JB.” The reverse is inscribed with the initials, “C.M.B.”

John Barry (fl. 1784-1827) Portrait sepia on ivory of father and daughter, c. 1785, with hairwork.

Charles Hayter (1761-1835) Maternal Allegory

I use the term "allegorical miniature" to denote full color miniatures that otherwise resemble sepias in their visual and thematic composition. This watercolor on ivory miniature, circa 1795, represents a mother with her son, dressed like Gainsborough's "Blue Boy," and daughter, dressed like Lawrence's "Pinky," resting on a bench in an Arcadian landscape.

Hayter served as Teacher of Perspective to Princess Charlotte. The above miniature displays Hayter's short, compact, oblique brush strokes, blue shading to the recesses of the face especially the corners of the eyes, and the blue, green, yellow color scheme borrowed from “Newton’s rainbow” and intended to resonate with “the cold part of the iris” (Hayter 1815). The Maternal Allegory likewise illustrates several of Hayter’s (1815) fourteen enumerated rules to be observed in shading:

Rule 1

The greatest distance in an open scene, with a clear sky, will always be the palest…

3 The nearest objects, or those in the foreground of an open scene, will have the darkest shades…

5 To adapt the picture to the power and properties of the eye, you must, on all occasions, lay as tender, gradual, and imperceptible a shade as possible, at each corner of a square or oblong drawing, blending it sweetly off towards the point of sight, so as to give the surface a concave apperance. The same should be done towards the margin of a circular drawing; always securing this natural concave effect.

6 Always begin with pale tint of the sky and distant masses of shade; and as you approach the foreground, increase the depth of the tint, observing to be light enough at first.

7 When you require additional strength of shade, do not take a darker tint for that purpose, but repeat the use of the original tint; strengthening the shades of all the degrees of distance with its own tint, or the object will press too forward.

Tuesday, September 5, 2006

Hairwork Jewelry: Palette Worked Hair

“Drawing from his bosom a locket, which was attached to a slight steel chain, he opened it and showed me a tress of golden hair. “In this curl is clasped the history of my life, friend,’ he said, with calm sorrow. “’Tis only a woman’s hair,’ as poor Swift wrote once; yet it is this which has made me what I am. God rules us all. He makes us very weak, that, in our weakness, He may make His own strength perfect. To one comes joy and laughter; to another tears. I accept my part, and bow to Him who is Lord of all” – Anonymous, 1859

“Drawing from his bosom a locket, which was attached to a slight steel chain, he opened it and showed me a tress of golden hair. “In this curl is clasped the history of my life, friend,’ he said, with calm sorrow. “’Tis only a woman’s hair,’ as poor Swift wrote once; yet it is this which has made me what I am. God rules us all. He makes us very weak, that, in our weakness, He may make His own strength perfect. To one comes joy and laughter; to another tears. I accept my part, and bow to Him who is Lord of all” – Anonymous, 1859Jewelry incorporating human hair have been in existence since at least the 1500s. They probably share a cultural lineage with Christian relics, which housed various body parts of saints or martyrs and were believed to possess spiritual power. Early hairwork jewelry from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were frequently love tokens or mourning jewelry incorporating the hair of a loved one rather than a saint, and they often included momento mori symbolism. Hairwork jewelry became popular in Europe and America after 1760 and extremely popular after the industrial revolution provided the middle classes with less expensive, mass produced jewelry findings. It is a common mistake to assume that all hairwork jewelry were mourning objects. In this latter period, hairwork jewelry provided a sentimental memorial to love, friendship, family, celebrity, and, of course, mourning.

Hairwork jewelry designed and executed on an artist’s palette is referred to as “palette worked.” The designs produced by palette work range from simple basket weaves to extremely intricate and symbolic or allegorical scenes.

Illustration plate demonstrating a step in the art of palette working hair from Alexanna Speight's (1872) The Lock of Hair.

Georgian brooch containing two palette worked curls mounted on blue enamel backed by embossed foil.

This pendent brooch contains a palette worked forget-me-not and curl on translucent milk glass backed by embossed red foil.

On the reverse, there are two hairwork curls each labeled with initials, “E.O.” and “H.C.O.,” spelled out in tiny seed pearls on translucent blue enamel plaques backed with embossed foil.

This brooch contains a beautiful palette worked feather sculpted from red hair with flower, branch, and the initials “B.P.” on opalescent glass.

Hairwork Jewelry: Palette Worked Hair

“Drawing from his bosom a locket, which was attached to a slight steel chain, he opened it and showed me a tress of golden hair. “In this curl is clasped the history of my life, friend,’ he said, with calm sorrow. “’Tis only a woman’s hair,’ as poor Swift wrote once; yet it is this which has made me what I am. God rules us all. He makes us very weak, that, in our weakness, He may make His own strength perfect. To one comes joy and laughter; to another tears. I accept my part, and bow to Him who is Lord of all” – Anonymous, 1859

“Drawing from his bosom a locket, which was attached to a slight steel chain, he opened it and showed me a tress of golden hair. “In this curl is clasped the history of my life, friend,’ he said, with calm sorrow. “’Tis only a woman’s hair,’ as poor Swift wrote once; yet it is this which has made me what I am. God rules us all. He makes us very weak, that, in our weakness, He may make His own strength perfect. To one comes joy and laughter; to another tears. I accept my part, and bow to Him who is Lord of all” – Anonymous, 1859Jewelry incorporating human hair have been in existence since at least the 1500s. They probably share a cultural lineage with Christian relics, which housed various body parts of saints or martyrs and were believed to possess spiritual power. Early hairwork jewelry from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were frequently love tokens or mourning jewelry incorporating the hair of a loved one rather than a saint, and they often included momento mori symbolism. Hairwork jewelry became popular in Europe and America after 1760 and extremely popular after the industrial revolution provided the middle classes with less expensive, mass produced jewelry findings. It is a common mistake to assume that all hairwork jewelry were mourning objects. In this latter period, hairwork jewelry provided a sentimental memorial to love, friendship, family, celebrity, and, of course, mourning.

Hairwork jewelry designed and executed on an artist’s palette is referred to as “palette worked.” The designs produced by palette work range from simple basket weaves to extremely intricate and symbolic or allegorical scenes.

Illustration plate demonstrating a step in the art of palette working hair from Alexanna Speight's (1872) The Lock of Hair.

Georgian brooch containing two palette worked curls mounted on blue enamel backed by embossed foil.

This pendent brooch contains a palette worked forget-me-not and curl on translucent milk glass backed by embossed red foil.

On the reverse, there are two hairwork curls each labeled with initials, “E.O.” and “H.C.O.,” spelled out in tiny seed pearls on translucent blue enamel plaques backed with embossed foil.

This brooch contains a beautiful palette worked feather sculpted from red hair with flower, branch, and the initials “B.P.” on opalescent glass.

Hairwork Jewelry: Table Worked Hair

The revival of hairwork jewelry in the 1980-90s has revealed that the equipment and basic patterns for table work hair braiding are identical to kumihimo braiding in Japan. Kumihimo braiding was used to construct durable silk cords for clothing and samurai armor from at least 700 AD to the present. However, this method of working hair was probably independently invented in Europe and shares no lineage with Japanese kumihimo. It nevertheless uses the same technique of weighted hair strands joined by a counter weight and passed back and forth across different quadrants of the tabletop.

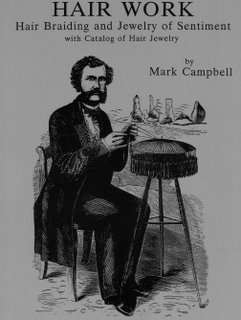

The revival of hairwork jewelry in the 1980-90s has revealed that the equipment and basic patterns for table work hair braiding are identical to kumihimo braiding in Japan. Kumihimo braiding was used to construct durable silk cords for clothing and samurai armor from at least 700 AD to the present. However, this method of working hair was probably independently invented in Europe and shares no lineage with Japanese kumihimo. It nevertheless uses the same technique of weighted hair strands joined by a counter weight and passed back and forth across different quadrants of the tabletop. Frontispiece from Mark Campbell's (1875) The Art of Hairwork: Hair Braiding and Jewelry of Sentiment illustrating the table stand used to create hairwork braids.

A table work pattern from The Art of Hairwork

Lacis has republished Mark Campbell's books and Alexanna Speight's (1872) The Lock of Hair, which are available through their website. Lacis also has a store in Berkley filled with an amazing selection of books and supplies for the whole spectrum of art and craft textiles and adornment. The staff is freindly, helpful, and willing to share their passion and enthusiasm for all things related to antiques and dress. Check out their website: Lacis

This brooch and earrings set was constructed with the table work method using a pattern for a hollow open work braid.

This watch chain was constructed from two different patterns for solid chains, which were then braided together. The hairwork beads encased in gold wire were crafted using a hollow open work pattern.

The hairwork beads suspend a double-sided locket with two different palette worked hair designs on each side.

This engraving of the same watch chain pictured above comes from the catalog pages of Mark Campbell’s 1875 how-to book for the amateur hairworker.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)